NeXus #0002

The weekly supplement for extra goodies.

The weekly supplement for extra goodies.

Around the Web:

Thisissand

Thisissand is a unique playground for creating and sharing amazing sandscapes on your computer or mobile device. Start pouring away to experience this special sand piling on your screen!

WindowSwap

Open a new window somewhere in the world

Articles:

Why 21 cm is our Universe’s “magic length”

Photons come in every wavelength you can imagine. But one particular quantum transition makes light at precisely 21 cm, and it’s magical.

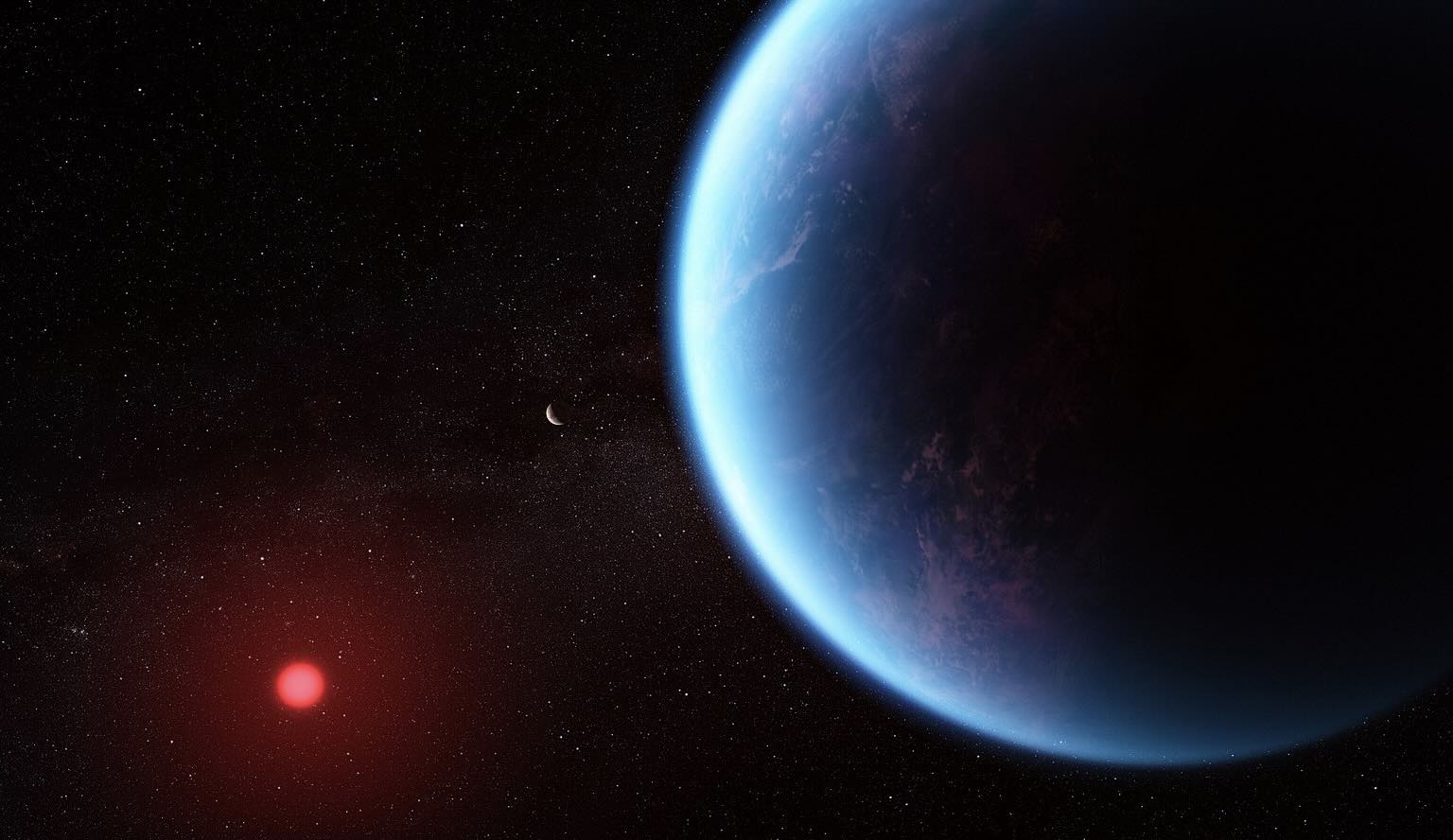

Is the universe really infinite? Astrophysicists explain.

How we understand the wider cosmos from our tiny observable bubble of space.

Ask Ethan: What right do we have to colonize other worlds?

In all the known Universe, Earth is the only planet known to have native life. What should guide us in expanding humanity beyond our world?

‘It blew us away’: how an asteroid may have delivered the vital ingredients for life on Earth

Extraterrestrial rocks, recently delivered by a space probe, could answer the big questions about alien lifeforms and human existence

Engineers Found Evidence of Hydraulics in an Ancient Pyramid, Solving a 4,500-Year-Old Mystery

See how Egyptian engineers might have used water to shape history’s greatest monuments.

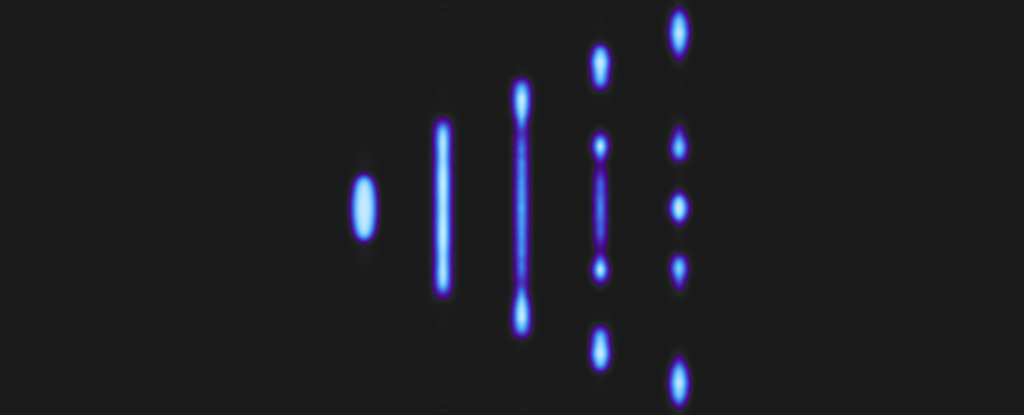

Amazing Physics Experiment Reveals ‘Quantum Rain’ For The First Time

As strange and unique as the laws of the quantum realm appear in our everyday experience, every now and then experiments catch sight of phenomena that seem both alien and yet eerily familiar.

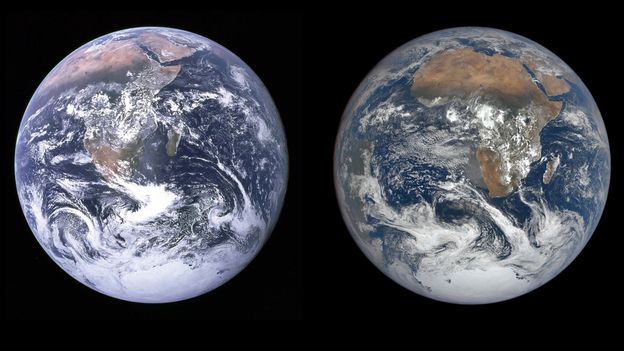

How 50 years of climate change has changed the face of the ‘Blue Marble’ from space

The “Blue Marble” was the first photo of the whole Earth and the only ever taken by a human. Fifty years on, new images of the planet reveal visible changes to the Earth’s surface.

Water-powered gadgets may be on the horizon thanks to new evaporation-based energy device - Advanced Science News

Scientists created an “evapolectrics” generator that draws power directly from water evaporation, offering a sustainable, battery-free energy source from humidity.

AI-controlled fighter jets may be closer than we think — and would change the face of warfare

The US military is already using AI to control aircraft in tests.

Google’s New AI Is Trying to Talk to Dolphins—Seriously

A new AI model produced by computer scientists in collaboration with dolphin researchers could open the door to two-way animal communication.

You Are Not an Ape-Brained Meat Sack

In quantum mechanics, a physics that cares

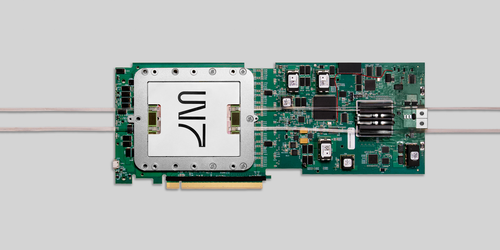

Photonic Computing Takes a Step Toward Fruition

Two newly developed computer chips, powered in part by light, have tackled complex computing tasks once considered out of reach for photonic systems.

Heads detached, battery ran out: 70% humanoids failed in robot marathon

Of the twenty-one robots that competed in the first human-robot half-marathon in Beijing, only six completed it.

Could the Hidden Answer to Fermi’s Paradox Be Stealth AI Probes?

Where Is everybody? The answer to Fermi’s famous paradox may be lurking closer than we expected... and it could involve stealth AI probes.

Trial to boldly grow food in space labs blasts off

The mission will explore new ways of reducing the cost of feeding an astronaut.

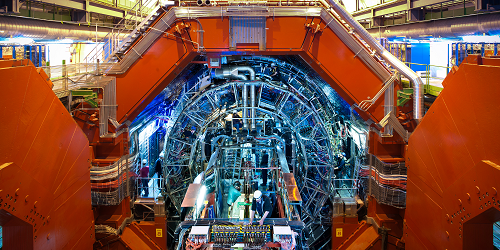

Evidence for an Exotic Antimatter Nucleus

Experiments at the Large Hadron Collider have revealed a previously unseen nucleus known as antihyperhelium-4.

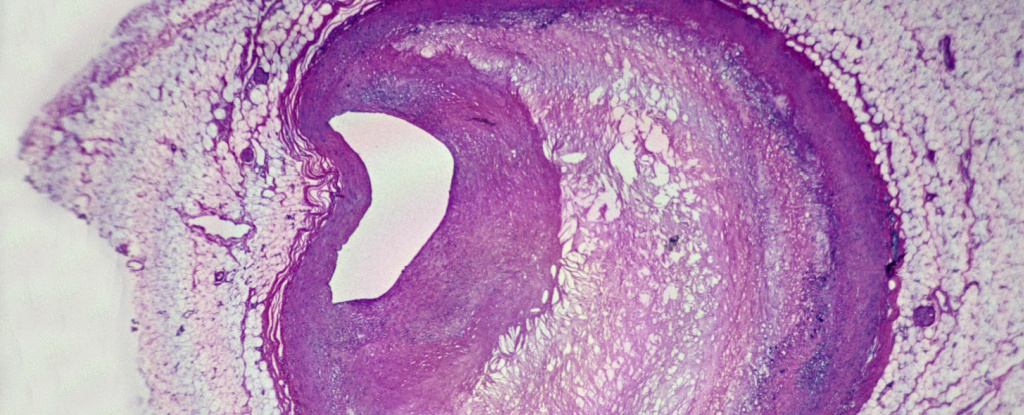

Study Reveals a Shocking Amount of Plastic in The Arteries of Stroke Patients

Tiny, microscopic bits of plastic have been found almost everywhere researchers look – including throughout the human body.

This Surprising Protein Shift Could Add Years to Your Life, Study Finds

A global study ties plant protein to longer adult lives, but early life needs differ.

Crows Are So Smart They Can Identify Geometric Shapes, Study Finds

Crows have a sense of geometric intuition much like our own, a new study reveals.

Consciousness reveals there’s no single objective world | Christian List

<p><em>Does reality contain only physical things? Or could everything be conscious, as panpsychists claim? Philosopher Christian List argues it’s time to move beyond both sides of this debate. Consciousness reveals something far more radical: reality cannot be captured by a single, objective description. Dualists, panpsychists and materialists all assume that there’s one unified reality that science and philosophy can aim to describe. But the deep subjectivity of consciousness shows this can’t be right. Reality cannot be contained in a single book – only a whole library of perspectives will do.</em></p><p> </p><p>Science has been hugely successful at explaining many phenomena, from the motion of the planets to the functioning of biological organisms. But despite advances in neuroscience, explaining how consciousness fits into the world remains elusive. Why do some organisms have experiences, feelings, subjective perceptions, and so on? The hallmark of consciousness is that <a href=“https://www.jstor.org/stable/2183914?origin=crossref” target=“_blank”>there is something it is like to be a conscious subject</a>, for that subject, as Thomas Nagel famously puts it. What makes some entities conscious, and others not, and how is consciousness related to the rest of the physical world? Even worse, there is no agreement on what would count as a good answer.</p><p>The big challenge of explaining consciousness stems from the fact that consciousness is inherently first-personal: something experienced only from a first-person perspective. Ordinary science, by contrast, is entirely third-personal. This point is widely appreciated, but its ramifications for our scientific worldview are more radical than commonly recognized. My claim is that, to capture what is special about consciousness, we must accept that there are genuinely first-personal facts, over and above the third-personal facts that ordinary science recognizes.</p><p>David Chalmers distinguishes between <a href=“https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/imp/jcs/1995/00000002/00000003/653” target=“_blank”>the “easy” and the “hard” problems of consciousness</a>. The “easy problems” are to explain the cognitive and behavioural functions related to consciousness and to figure out which brain processes underpin them. Examples of such functions are the difference between wakefulness and sleep, and the ability to respond to perceptual stimuli. These problems are “easy,” insofar as they can be approached using ordinary scientific methods. For example, scientists can use behavioural and verbal responses as external markers of consciousness and correlate these with other observable data, including data from brain scans and physiology. However, even if neuroscience will ultimately tell us which patterns of brain activity are associated with which cognitive functions, this leaves unanswered a more fundamental question: why are there conscious experiences at all? Why do certain physical processes in the brain and body give rise to subjective experiences? Why don’t these processes take place “in the dark,” without anyone having any experiences, just as the planets revolve around the sun without the solar system experiencing anything? Answering these questions is the “hard” problem. What makes it hard is that the thing to be explained, subjective experience, is first-personal, while ordinary science offers only third-personal explanations.</p><p class=“article-plus-content--header” style=“text-align: center;”>___</p><p class=“article-plus-content--header” style=“text-align: center;”>None of the physical and behavioural markers of consciousness that scientists study get to the heart of what consciousness is.</p><p class=“article-plus-content--header” style=“text-align: center;”>___</p><p>The hard problem can be illustrated by introducing the thought experiment of a <a href=“https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/zombies/” target=“_blank”>“philosophical zombie.”</a> This is a hypothetical being that displays all the physical and behavioural markers of consciousness without actually experiencing anything. No external observation, experiment, or brain scan could identify the difference between a zombie and a conscious being like you and me. The zombie looks like you and me, displays the same physical processes in the brain and body, and gives the same verbal responses. It is third-personally indistinguishable from you and me. From an observer’s perspective – even with the best scientific equipment – one can never strictly rule out the possibility that another organism is a zombie.</p><p> <span class=“article-content-box”> <a href=“video/darwin-vs-consciousness” class=“iai-related-in-article click_on_suggestion_link--gtm-track”> <span class=“iai-card”> <span class=“iai-card--image iai-related--video-play” style=“display: block;”> <img src=”/assets/Uploads/darwin-vs-consciousness.webp” class=“iai-related--primary-image” alt=“related-video-image”> </span> <span class=“iai-card--content” style=“display: block;”> <span class=“iai-card--title” style=“display: block;”>SUGGESTED VIEWING</span> <span class=“iai-card--heading” style=“display: block;”>Darwin vs consciousness</span> <span style=“display: block;”>With Güneş Taylor, Stuart Hameroff, Denis Noble, Antonella Tramacere</span> </span> </span> </a> </span> </p><p>Of course, no-one reasonably thinks that there are zombies in the real world. However, the thought experiment seems coherent. Though it’s science fiction, it involves no logical contradiction. What this thought experiment shows, arguably, is that none of the physical and behavioural markers of consciousness that scientists study get to the heart of what consciousness is. The consciousness that you and I have goes beyond the kinds of third-personally observable properties that science normally refers to. This has led some, including Chalmers, to take seriously the idea that to accommodate consciousness in a scientific worldview, we must postulate the existence of special kinds of “phenomenal” properties, over and above the ordinary physical properties recognized by science.</p><p>On Chalmers’s picture, <a href=“https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/imp/jcs/1995/00000002/00000003/653” target=“_blank”>incorporating consciousness into a scientific worldview</a> would require the kind of theoretical innovation that James Clerk Maxwell and others made when they first postulated the existence of electromagnetic fields. What Maxwell showed was that the inventory of properties that exist in the physical world was richer than previously recognized. There are not only the properties related to gravity and motion, as described by Isaac Newton, but also electromagnetic properties that were missing from earlier physical theories. Similarly, Chalmers has suggested, we must recognize that the world contains not only physical properties, but also some additional “phenomenal” properties, and these are responsible for conscious experiences. It is the existence of those non-physical phenomenal properties that makes the difference between the actual world, in which there is consciousness, and the hypothetical “zombie world,” in which everything is physically the same, but consciousness is missing. Chalmers’s position, developed in detail in an influential <a href=“https://philpapers.org/rec/CHATCM” target=“_blank”>1996 book</a>, is a modernized, “naturalistic” version of dualism. (Dualism of the more traditional sort, according to which the mind is a non-physical substance, distinct from the brain, is usually associated with René Descartes in the seventeenth century.)</p><p class=“article-plus-content--header” style=“text-align: center;”>___</p><p class=“article-plus-content--header” style=“text-align: center;”>Despite the disagreements between physicalists, dualists and others, practically all sides in this debate share one common assumption. This is the assumption that there is a unified objective world, which science and philosophy seek to describe and explain and in which all relevant properties can be found.</p><p class=“article-plus-content--header” style=“text-align: center;”>___</p><p>Against the dualists, <a href=“https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/physicalism/” target=“_blank”>physicalists</a> such as <a href=“https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262541916/sweet-dreams/” target=“_blank”>Daniel Dennett</a> deny that we must postulate any special phenomenal properties to account for consciousness. Our inability to explain how physical processes in the brain and body give rise to conscious experiences, they say, is due to the fact that neuroscience is insufficiently advanced. Our current inability to explain consciousness is like the inability of some nineteenth-century scientists to explain the phenomenon of life. Those scientists thought that one needed to postulate some special “vital spirit” to explain life, whereas we now know that this is unnecessary. Ordinary chemistry and biology suffice. Similarly, the reasoning goes, we will eventually understand how consciousness arises from physics, chemistry and biology alone, without having to throw any additional “phenomenal” properties into the mix.</p><p> <span class=“article-content-box”> <a href=“video/arc-of-life-daniel-dennett5″ class=“iai-related-in-article click_on_suggestion_link--gtm-track”> <span class=“iai-card”> <span class=“iai-card--image iai-related--video-play” style=“display: block;”> <img src=”/assets/Uploads/DD-thumbnail2.webp” class=“iai-related--primary-image” alt=“related-video-image”> </span> <span class=“iai-card--content” style=“display: block;”> <span class=“iai-card--title” style=“display: block;”>SUGGESTED VIEWING</span> <span class=“iai-card--heading” style=“display: block;”>Arc of life: Daniel Dennett</span> <span style=“display: block;”>With Daniel Dennett</span> </span> </span> </a> </span> </p><p>Much of the contemporary philosophical debate about consciousness revolves around the question just discussed: is consciousness ultimately explicable in terms of physical properties alone, or do we need something non-physical too? Might we even have to suppose that everything in our universe has both a physical aspect and a phenomenal one, as suggested by some versions of <a href=“http://iai.tv/articles/conscious-universe-panpsychism-idealism-goff-kastrup-auid-1584″ target=“_blank”>panpsychism</a>?</p><p>However, despite the disagreements between physicalists, <a href=“https://www.cambridge.org/core/elements/nonphysicalist-theories-of-consciousness/BD11AFA6D1ABF9EAD3597880C7E15DDB” target=“_blank”>dualists and others</a>, practically all sides in this debate share one common assumption. This is the assumption that there is a unified objective world, which science and philosophy seek to describe and explain and in which all relevant properties can be found. The disagreements are just about the precise inventory of that world. What exactly does that world contain? For example, are there only physical properties or also phenomenal ones? Given the heated nature of the debate, it is easy to miss the fact that there is nonetheless this shared assumption of an objective world.</p><p>What is the significance of this? It is that the conventional scientific and philosophical theories, including those dualist theories that were especially devised to account for consciousness (such as Chalmers’s), ultimately give us a third-personal picture of the world. They seek to describe and explain the world as it would be seen by an omniscient, or at least highly informed, outside observer: someone who is taking what Thomas Nagel has called “<a href=“https://philpapers.org/rec/NAGTVF” target=“_blank”>the view from nowhere</a>.”</p><p>The attempt to abstract away from any particular perspective is a central feature of modern science. By looking beyond the particularities of specific objects, events and perspectives, science has been able to uncover general patterns and regularities: ones that are “invariant” under shifts in perspective and that qualify as candidates for general laws of nature. The history of science illustrates the move towards greater abstraction. Over time, humans went from an anthropocentric to a geocentric to a heliocentric and eventually to a more universal view of the world, and each step constituted scientific progress.</p><p>Yet the crux is that there is at least one important phenomenon that resists such objectivization or “de-perspectivization,” and that is consciousness itself. If we accept that the core of consciousness is subjective experience, then consciousness is the ultimately subjective phenomenon. The core of my consciousness lies in the fact that I find myself in a world in which there are first-personal facts. I am conscious, I have certain experiences, I am in a particular perceptual state, and so on. First-personal facts are irreducibly subjective. They are “centred” around my perspective as an experiencing subject, and unlike objective facts, they are not invariant under shifts in perspective.</p><p>Crucially, each of us is inextricably tied to our own conscious perspective. I can reflect about your experiences and empathize with you; I can hypothetically try to place myself in your shoes; I can try to simulate in my mind what things must be like for you. But I cannot <em>literally</em> leave my own conscious perspective. It is an essential fact about me that I experience the world from my perspective and not from anyone else’s. To be conscious, one might say, is to have a subjective perspective around which some first-personal facts are centred.</p><p> <span class=“article-content-box”> <a href=“video/the-divided-self-sam-harris-roger-penrose” class=“iai-related-in-article click_on_suggestion_link--gtm-track”> <span class=“iai-card”> <span class=“iai-card--image iai-related--video-play” style=“display: block;”> <img src=”/assets/Uploads/the-divided-self-1.webp” class=“iai-related--primary-image” alt=“related-video-image”> </span> <span class=“iai-card--content” style=“display: block;”> <span class=“iai-card--title” style=“display: block;”>SUGGESTED VIEWING</span> <span class=“iai-card--heading” style=“display: block;”>The divided self</span> <span style=“display: block;”>With Roger Penrose, Jack Symes, Sam Harris, Sophie Scott</span> </span> </span> </a> </span> </p><p>A number of philosophers – <a href=“https://doi.org/10.1093/pq/pqae053″ target=“_blank”>myself included</a> – have argued that unless we recognize the existence of such first-personal facts, we cannot adequately describe and explain the phenomenon of conscious experience. For the phenomenologists in the tradition of <a href=“https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/husserl/” target=“_blank”>Edmund Husserl</a>, the first-person perspective was the starting point of any enquiry. Without that perspective, our worldview would be incomplete. Among contemporary philosophers, <a href=“https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/9780262035552.003.0010″ target=“_blank”>Dan Zahavi</a>, for instance, writes: “[S]ubjectivity is a built-in feature of experiential life. Experiential episodes are neither unconscious, nor anonymous, rather they necessarily come with first-personal givenness or perspectival ownership.” And <a href=“https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199914722.001.0001” target=“_blank”>Lynne Rudder Baker</a> writes that the scientific worldview “takes the world to be impersonal; what exists are all individuals and all their properties, but none of these requires appeal to anything expressible in the first person.” And she asks how such an impersonal world could “accommodate me.” Her answer is that, to accommodate a subject’s perspective, we must recognize that “there are irreducible first-person facts.”</p><p>Similarly, Thomas Nagel argues that a purely third-personal view of the world <a href=“https://www.jstor.org/stable/2183358?origin=crossref” target=“_blank”>leaves out the fact that each of us is who we are</a>. It gives us a “description of all [of the world’s] physical contents and their states, activities, and attributes” and “a description of all the persons in the world and their histories, memories, thoughts, sensations, perceptions, intentions.” But even when the world has been fully described like this, he notes, “there seems to remain one fact which has not been expressed, and that is the fact that I am Thomas Nagel.”</p><p class=“article-plus-content--header” style=“text-align: center;”>___</p><p class=“article-plus-content--header” style=“text-align: center;”>If we cannot adequately explain consciousness without postulating irreducibly first-personal facts, there simply is no single objective book of the world.</p><p class=“article-plus-content--header” style=“text-align: center;”>___</p><p>To see the ramifications of these points, it is helpful to introduce the metaphor of the “book of the world.” This is a hypothetical massive book that contains a complete enumeration of all the facts that obtain in the world. It exhaustively describes everything that is the case in the world, up to the most minute detail, as it would be seen by an omniscient observer. According to the standard worldview in science and philosophy, as Theodore Sider summarizes it, “[t]here is an objectively correct way to <a href=“https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199697908.001.0001” target=“_blank”>‘write the book of the world’</a>.” It might be hard to figure out what it is, but the goal of science and philosophy is to write that book. Now, everyone understands that the complete book of the world can never be written in finite time and that we will only ever approximate part of it. But as a theoretical goal, it is widely assumed that there is in principle an objectively correct way to write that book.</p><p>However, if we cannot adequately explain consciousness without postulating irreducibly first-personal facts, there simply is no single objective book of the world. As it is conventionally characterized, that book is written from a third-person perspective. Its narrator is an Olympian observer describing the world from the outside. Such a book would fail to include any first-personal facts. It would be incomplete. So, it wouldn’t be <em>the book of the world</em>. For example, it would describe Christian and his experiences in third-personal terms, just as it would describe everyone else’s experiences in third-personal terms, but it would leave out the first-personal fact that I am having Christian’s experiences rather than anyone else’s. A complete inventory of reality, which includes subjective facts, could not be given in the form of a unified objective book.</p><p class=“article-plus-content--header” style=“text-align: center;”>___</p><p class=“article-plus-content--header” style=“text-align: center;”>The attempt to “objectivize” consciousness – to represent it as an ordinary property that can be found in the objective world, like gravity and electromagnetism – fails to do justice to the irreducibly subjective nature of the phenomenon.</p><p class=“article-plus-content--header” style=“text-align: center;”>___</p><p>Rather, it would require an entire library, consisting of <a href=“https://doi.org/10.1111/nous.12408” target=“_blank”>one subjective book for each conscious subject</a>. Each such book wouldn’t be written by an Olympian third-personal narrator, but it would reflect the first-person perspective of the relevant subject. My book of the world, which might be titled “The world as I found it” (as <a href=“https://www.gutenberg.org/files/5740/5740-pdf.pdf” target=“_blank”>Ludwig Wittgenstein</a> once proposed), would be different from yours, since it would be centred around my perspective, while your book would be centred around yours. To be sure, different such books would have some chapters in common, namely those that cover only objective facts – those that are invariant under shifts in perspective – such as the ordinary physical facts. But the different books would come apart in their subjective content. They could not be coherently merged into a single book because such a merged book could not be narrated from a unified perspective. (I assume that any potential book of the world must be coherent.)</p><p>The lesson, I think, is that the attempt to “objectivize” consciousness – to represent it as an ordinary property that can be found in the objective world, like gravity and electromagnetism – fails to do justice to the irreducibly subjective nature of the phenomenon. Physicalist theories of consciousness are not alone in running into that problem; standard versions of dualism face the same problem too. We will better understand consciousness only if our scientific and philosophical theories fully come to terms with the existence of first-personal facts and recognize that reality may not be captured by a single objective book of the world, but only by a library of subjective ones.</p><p><strong> </strong></p><p><strong>Author’s note:</strong> This article draws on two published papers of mine (<a href=“https://doi.org/10.1111/nous.12408” target=“_blank”>here</a> and <a href=“https://doi.org/10.1093/pq/pqae053” target=“_blank”>here</a>), where I have defended a “many-worlds theory” of consciousness and where more detailed literature references can be found. Fellow travellers in the exploration of first-personal facts, in addition to those mentioned above, include <a href=“https://doi.org/10.1093/0199278709.003.0009” target=“_blank”>Kit Fine</a>, <a href=“https://doi.org/10.5840/jphil2007104717” target=“_blank”>Caspar Hare</a>, <a href=“https://doi.org/10.1093/analys/ans101” target=“_blank”>Benj Hellie</a>, <a href=“https://doi.org/10.1111/1746-8361.12153” target=“_blank”>Giovanni Merlo</a>, <a href=“https://doi.org/10.3998/ergo.4649” target=“_blank”>Martin Lipman</a>, and <a href=“https://doi.org/10.1111/phc3.12959” target=“_blank”>David Builes</a>. Earlier critics of the assumption that there is a unique objective world include <a href=“https://doi.org/10.15173/jhap.v7i6.3827” target=“_blank”>Nelson Goodman</a>, <a href=“https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-005-8366-4” target=“_blank”>Gabriel Vacariu</a>, <a href=“https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198714385.001.0001” target=“_blank”>Ted Honderich</a>, and <a href=“https://philpapers.org/rec/GABWTW-2”>Marcus Gabriel</a>. I am very grateful to Daniel Stoljar and Laura Valentini for helpful feedback and to Philip Pettit for suggesting the “library” metaphor.</p>

Brains Scans Reveal What Really Happens When Your Mind Goes Blank

Scientists argue that blanking out is its own state of consciousness, distinct from having your mind wander off.

When AIs do science, it will be strange and incomprehensible | Aeon Essays

When AI takes over the practice of science we will likely find the results strange and incomprehensible. Should we worry?

5 classic science fiction novels written by scientists

“Write what you know” is good advice. So, what happens when scientists write what they know? Some amazing science fiction stories.

Trailers:

Photos:

🔴

Nexus is a weekly selection of content elsewhere shared by their creators and hereby suggested by me. Please give the original authors their due recognition by supporting their work.